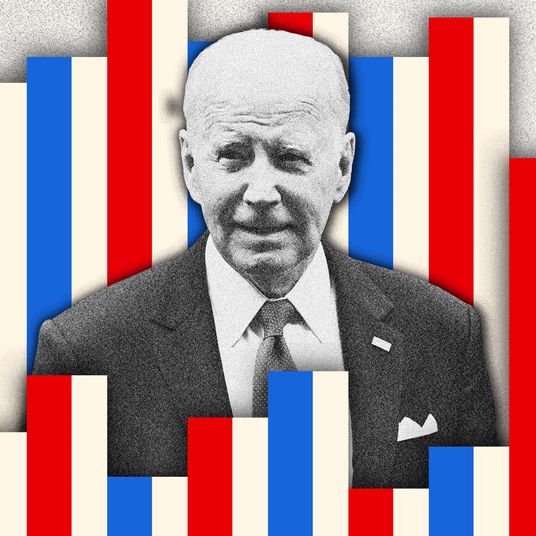

Two and a half years ago, Americans of good conscience watched in horror as thousands of supporters of Donald Trump stormed the U.S. Capitol, assaulted law-enforcement officers, and attempted to prevent the peaceful transition of power after he decisively lost the 2020 presidential election to Joe Biden. The Justice Department has since criminally charged more than 1,000 people for their conduct that day, but on Tuesday, Special Counsel Jack Smith finally added to the long list Trump himself, the person most responsible as a political, moral, and practical matter for the violent and outrageous attack on our democracy that day.

Trump’s indictment in Washington, D.C., is a watershed moment for our country, and it sets in motion the most important criminal prosecution in the nation’s history. The situation is all the more notable because the case is set against the backdrop of an election that may once again pit Biden against Trump — a campaign that could ultimately turn out, in a very real sense, to be about whose administration will send their opponent to prison.

The indictment technically contains four counts, but it tells a single and remarkable story about how Trump “lost the 2020 election” but “was determined to remain in power,” so he “spread lies” about pervasive election fraud that had supposedly robbed him of his rightful victory. His purpose “was to overturn the legitimate results of the 2020 presidential election by using knowingly false claims of election fraud to obstruct the federal government function by which those results are collected, counted, and certified.”

The means by which Trump allegedly did this will be familiar to anyone who closely followed last summer’s January 6 hearings in Congress: Trump pressured state election officials to ignore their election results and assign their electoral votes to Trump despite his loss, participated in organizing “fraudulent slates” of pro-Trump electors in seven states he lost to Biden, worked with the Justice Department official Jeffrey Clark to try to enlist the DOJ in his effort, lobbied Vice-President Mike Pence to throw the election to him in the joint session of Congress on January 6, 2021, and continued to pressure members of Congress to help overturn the election, even while the Capitol was under siege by his supporters. In fact, with one important exception, the indictment broadly tracks the opening statement that Liz Cheney, the January 6 committee vice-chair, made in the committee’s first hearing last summer, in which she argued that Trump “oversaw a sophisticated seven-part plan to overturn the 2020 election and prevent the transition of presidential power.”

On the basis of all this, the indictment charges Trump with violating three different criminal conspiracy statutes: conspiracy to defraud the government, conspiracy to obstruct an official government proceeding (the certification of the electoral count on January 6), and conspiracy to impair others’ federal rights (in this case, “the right to vote, and to have one’s vote counter”). There is also a fourth, so-called substantive count for obstructing, or attempting to obstruct, an official government proceeding.

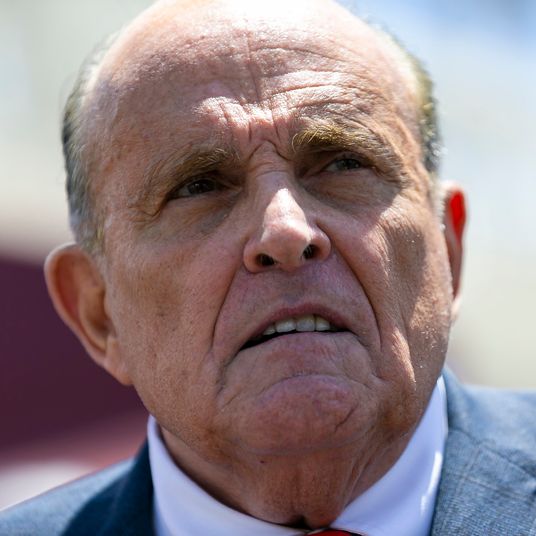

Trump’s alleged co-conspirators are apparently uncharged and unnamed for the moment, but that could change. (Department policy prohibits naming unindicted co-conspirators in an indictment.) The alleged co-conspirators appear to include Rudy Giuliani, John Eastman, Sidney Powell, and Clark, and if they are not affirmatively cooperating, they should prepare to be indicted at some point. One strategic reason not to include them all in this case, from a prosecutor’s perspective, is that adding defendants means that you are multiplying the number of defense lawyers and issues that may need to be litigated in this proceeding, and speed should be of the essence here to bring the case to trial before the conclusion of the 2024 election.

The most glaring difference between the indictment and the January 6 committee’s theory of the case is that prosecutors do not allege that Trump was aware of or involved in the planning for violence at the Capitol, and they do not allege that he incited the siege that day by telling his supporters to march to the Capitol. The committee strongly implied that Trump might bear some criminal responsibility for the violence that day, and many people were riveted by the testimony of White House aide Cassidy Hutchinson on this point, but despite the usual overheated punditry, the committee was ultimately unable to offer clear and incontrovertible evidence.

That would not have been easy for the committee to come by under the circumstances, but it is safe to assume that Smith and his team attempted to further run this down before concluding their work, and the omission is therefore notable. In fact, it seems as though the Justice Department ultimately wanted to steer clear of any suggestion in the indictment that Trump participated in planning the violence or that he incited the siege.

Instead, the core theory of the indictment is that Trump was intentionally lying about election fraud in order to try to stay in office. Prosecutors do not appear to have obtained evidence of any clear and contemporaneous admissions from Trump about the fact of his loss, but despite what Trump supporters are already claiming, this is not a fatal defect with the case.

Prosecutors often have to rely on circumstantial evidence and common sense to establish that a defendant intentionally lied. In this case, the circumstantial evidence includes the array of people who told Trump that he had lost, such as his own administration officials, advisers, and campaign team (people who shared his interest in reelection); the consistent and frequent admonitions on this point that Trump received; the self-serving and nonsensical nature of Trump and his allies’ fraud claims; and the fact that Trump had been laying the groundwork for months before the election to claim that it had been stolen from him. There are also some alleged comments from Trump that suggest he knew he had lost, as when he told senior Justice Department officials during a call in late December 2020 to “just say that the election was corrupt and leave the rest to me and the Republican congressmen.” Ultimately, a jury would weigh all of this evidence — including any evidence offered by Trump to suggest that he was simply relying on people like Giuliani and Eastman or that he actually believed the ridiculous claims he made — in rendering its verdict.

There will be plenty of time in the weeks and months ahead to engage in legal handicapping and pontification, but despite the undeniably historic nature of the indictment, it would be unwise as a matter of legal Realpolitik to assume that there is a straight path from here to conviction in this truly singular case.

The statute concerning obstruction of an official proceeding (the election certification in Congress) used by prosecutors against Trump has been central to the Justice Department’s effort to prosecute people who were present at the Capitol, but there are unsettled questions about whether and to what extent that provision can be used against people who were not engaged in violence or other forms of serious, on-the-ground misconduct. Trump, for instance, is not charged with planning or facilitating the violence at the Capitol, but prosecutors allege that he “exploited the disruption by redoubling efforts” to lobby members of Congress to throw the election to him; the trial or appeals court would likely need to determine at some point whether, as a legal matter, conduct like that is prohibited by the statute (even assuming the allegations are true). The Supreme Court could also intervene either before or after a trial, both because the conservative majority does whatever it wants and because the Court, more generally, has imposed very narrow readings on criminal statutes that prosecutors have tried to use to punish political offenses.

Alas, we also have the political calendar to contend with once again. According to the most recent data available, the median time it takes for a felony criminal case in Washington, D.C., to proceed to disposition is nearly 19 months. (Indeed, that number likely significantly understates the average timeline in a case that proceeds to trial since the figure includes cases that are resolved through guilty pleas.) That means that Trump may have plenty of time to complete his reelection bid and shut the case down if he manages to win the Republican nomination and then the general election next November. He could pull off the same remarkable feat even if the case manages to proceed to trial next year since he would likely be allowed to remain free while any posttrial and appeal proceedings are pending. This unfortunate situation is one result of the highly regrettable delay on the part of the Justice Department in focusing on Trump, which does not seem to have happened until the January 6 committee’s hearings effectively forced the department’s hand last summer.

On the other hand, the prosecution has some considerable advantages over the other pending criminal cases against Trump. The public is broadly familiar with Trump’s underlying conduct — an outrageous attempt to subvert the country’s democratic process at the highest level that he openly talked about — and it is not hard to understand why prosecutors and conscientious Americans would take it extremely seriously. If you were going to send a former president to prison for some reason, this would be a particularly good one.

Prosecutors also drew U.S. district judge Tanya S. Chutkan as the presiding judge. She has been both admirably consistent and appropriately outraged in her handling of January 6 cases, and she may be more amenable than most judges in the district to an accelerated timeline that might actually result in a trial next year.

The jury pool in Washington — where voters almost unanimously preferred Biden to Trump in 2020 — is also much more favorable to federal prosecutors than the one in Florida, where the prosecution against Trump for mishandling classified documents and obstructing investigators is pending. Trump and his de facto supporters — including the ones who are supposedly running to defeat him in the Republican primary, like Ron DeSantis — like to complain about this, but the government is legally required to charge defendants in the district in which they committed their offenses, which means that the person most responsible for choosing where someone is criminally charged is usually the defendant themself. (If you do not want to be tried in federal court in D.C., my very sincere advice is that you should not engage in conduct that may violate federal criminal laws in D.C.)

More important, any inherent legal risks and uncertainties of this prosecution are well worth confronting as part of a federal prosecution that is otherwise justified on every conceivable ground. As a straightforward punitive matter, Trump deserves to be sanctioned for his extraordinary selfishness, megalomania, and corruption, including for the turmoil that he put the country through in the months leading up to and after January 6, continuing even to this day. As a matter of due process and political hygiene, the country deserves a rigorous mechanism to resolve Trump’s criminal culpability both now and for the history books.

A successful prosecution will also deter future presidents and government officials from engaging in serious, politically destructive abuses of power no matter how factually novel or legally innovative they may seem to be. And as a constitutional matter, there may be no greater testament to a country’s legal system or structural health than the ability to hold the nation’s most powerful leaders to account for their misdeeds.

This is a vital case for the long-term strength of our democracy, but Trump’s reelection bid, his obnoxious and uncontrollable mouth, and his ability to rally many of his supporters around the most preposterous and self-serving claims will make this harder for the Justice Department. Republican primary voters could conceivably spare us all a huge mess — and effectively allow this case and the one in Florida to reach an orderly resolution — if they would just nominate someone else as their standard-bearer for 2024, but even that is increasingly questionable thanks to the distinct possibility that another Republican would simply pardon Trump upon taking office.

Lawyers often like to talk about the distinction between law and politics, but in many of the most important cases, the distinction is harder to detect and to manage than we would like to believe. This case is undeniably about both law and politics — in the most important and the most defensible senses. Let’s hope that it reaches the resolution that the country deserves: with Trump held legally and fully accountable for his alleged crimes against America and against our democracy.

More on the Trump January 6 indictment

- Trump Did Not Luck Out With the Judge in His January 6 Case

- Six Co-Conspirators in January 6 Indictment Have Been Identified: Live Updates

- January 6 Was ‘Right Out of the Giuliani Playbook’